The Texas Spring Palace

By Max Levy Domain Magazine April 1989

It is January, 1889. Survival on the Texas land has become routine, and prosperity abounds. Taking pride in this conquest of a formidable frontier, a group of Fort Worth business leaders resolve to celebrate with a state exposition. Texans’ mastery of a region rich in history, natural resources, and human ambition will now be displayed to the world.

Participation in this endeavor is recruited statewide and supporters call for a new building to house the enthusiasm. The prominent Fort Worth architectural firm of Armstrong and Messer offers its services free of charge to assure its role in the prestigious project. The architects design a most uncommon building. Its exterior shell is to be erected by the City of Fort Worth, its ornamentation to be contributed by each county, and the displays are to come from every willing Texas town, organization, and company.

In March the Fort Worth Loan and Construction Company wins the contract to build the exhibition hall, with the stipulation that the immense wooden structure is to be completed in forty days or all compensation will be forfeited. The contractors agree to the strict clause, even though when foundation work begins, the project’s lumber still stands in East Texas forests, waiting to be cut down, milled, and conveyed to Fort Worth.

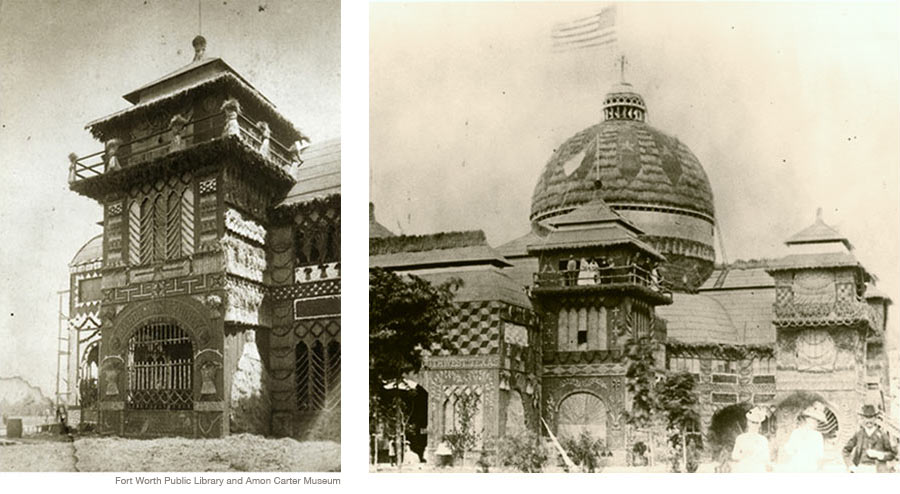

Amazingly, the construction is completed on schedule. Devoid of any decoration, the entire complex of wood-sheathed framing is painted a dark bronze-green. During the brief interval before ornamentation work begins, the building’s dark hulk resembles a barren architectonic mountain standing at the edge of town.

But as the ornamentation is applied, the building’s curious character comes to life. The process requires more time than the construction did, and three times as many workers. Instead of shingles, stone, clapboards, and brick, the entire surface of the building is covered inch by inch with a harvest of raw materials representing every region of the state. From farming counties come sixteen railroad cars of wheat, seven cars of millet, two cars of cane, four cars of broomcorn, rye, and sorghum, two cars of cotton and wool, ten acres of cornstalks, and eight acres of alfalfa and Johnson grass. From the state’s prairies, hills, and coast come four cars of mosses, oleanders, and shrubbery, four cars of cacti, four cars of cedar, four cars of coal and other minerals, one car of seashells, and one car of pelts and hides. And finally, from the ranching counties come an unspecified quantity of cattle horns, skulls and one taxidermized steer. Even the roofing is specially altered: In place of gravel, shelled corn and oats are embedded in the tar.

It is January, 1889. Survival on the Texas land has become routine, and prosperity abounds. Taking pride in this conquest of a formidable frontier, a group of Fort Worth business leaders resolve to celebrate with a state exposition. Texans’ mastery of a region rich in history, natural resources, and human ambition will now be displayed to the world.

Participation in this endeavor is recruited statewide and supporters call for a new building to house the enthusiasm. The prominent Fort Worth architectural firm of Armstrong and Messer offers its services free of charge to assure its role in the prestigious project. The architects design a most uncommon building. Its exterior shell is to be erected by the City of Fort Worth, its ornamentation to be contributed by each county, and the displays are to come from every willing Texas town, organization, and company.

In March the Fort Worth Loan and Construction Company wins the contract to build the exhibition hall, with the stipulation that the immense wooden structure is to be completed in forty days or all compensation will be forfeited. The contractors agree to the strict clause, even though when foundation work begins, the project’s lumber still stands in East Texas forests, waiting to be cut down, milled, and conveyed to Fort Worth.

Amazingly, the construction is completed on schedule. Devoid of any decoration, the entire complex of wood-sheathed framing is painted a dark bronze-green. During the brief interval before ornamentation work begins, the building’s dark hulk resembles a barren architectonic mountain standing at the edge of town.

But as the ornamentation is applied, the building’s curious character comes to life. The process requires more time than the construction did, and three times as many workers. Instead of shingles, stone, clapboards, and brick, the entire surface of the building is covered inch by inch with a harvest of raw materials representing every region of the state. From farming counties come sixteen railroad cars of wheat, seven cars of millet, two cars of cane, four cars of broomcorn, rye, and sorghum, two cars of cotton and wool, ten acres of cornstalks, and eight acres of alfalfa and Johnson grass. From the state’s prairies, hills, and coast come four cars of mosses, oleanders, and shrubbery, four cars of cacti, four cars of cedar, four cars of coal and other minerals, one car of seashells, and one car of pelts and hides. And finally, from the ranching counties come an unspecified quantity of cattle horns, skulls and one taxidermized steer. Even the roofing is specially altered: In place of gravel, shelled corn and oats are embedded in the tar.

Christened the Texas Spring Palace, the building opens on May 29, 1889. Texans are satisfied that they have erected the most beautiful building in the world. They overlook a concurrent exposition across the Atlantic, where a man named Eiffel has just completed a remarkable tower. In colors and textures that resemble a gargantuan dried flower arrangement, the Spring Palace is an earthy monument. The Fort Worth Gazette observes, “Viewed from the distance of Front Street the Spring Palace appears the work of a genii… With its oriental towers silhouetted against the blue vault beyond, the rich, deep colors glistening in the sun, the banners flaunting in the gentle Texas breezes, music floating dimly in entrancing wavelets, the stranger is apt to stop short.”

Inside, the building’s walls are adorned in a continuation of the fantastic exterior. Against this backdrop, all of Texas is displayed with exuberant pride. The crazy-quilt floor plan of nooks and crannies bristles with exhibits of native woods, stone, and brick; minerals and ores; food, fibers, flowers, and furniture; insects, snakes, and lizards; a log cabin, a tepee, and a cave; historic relics, Texas patents, silkworms at work, and hundreds of live songbirds. What cannot be displayed firsthand is reproduced in large mosaic pictures and models, each fancifully rendered in native seeds, nuts, fish scales, or butterfly wings. In the rotunda, next to a large fountain stocked with game fish and ducks, the Elgin Watch Factory Band plays almost constantly. A local journalist calls the Palace “a bower of bewilderment.”

Advertised all across the nation, the Palace becomes an immediate tourist attraction—trains deliver the curious daily. Large registers at the Palace entrance record the arrival of visitors from every state in the nation. Though open for only three weeks, the exhibition is a fabulous success, and a second season is planned for the spring of 1890. An Austin newspaper writer dizzy with excitement editorializes (to no avail) that duplicates of the Palace be built in Chicago and New York City.

In its long off-season the Palace stands exposed to a year of weather. In the absence of flags flapping and bands playing, the wind can now be heard rustling the wheat that sheathes the huge central dome. On winter mornings the Palace waits silently, dusted with frost.

Two 100-foot-long extensions are added to the building for the 1890 season, and the hoopla continues. But on the evening of May 30th, during a grand ball in the Palace attended by thousands, the inevitable occurs. No one knows how the fire starts, but the building is quickly consumed like the architectural version of a prairie wildfire. Somehow, despite the disaster’s magnitude, there is only one fatality, a man who dies while rescuing others trapped in the Palace. It is a blaze of milestone proportions: At a time when America swoons at romantic calamities, the destruction of the Palace is front-page news nationwide. In fact, the death of the Texas Spring Palace is so spectacular that it overshadows accounts of the building’s fascinating life for nearly one hundred years. Those who remember, remember only the fire, while the “bower of bewilderment” is all but forgotten.

Christened the Texas Spring Palace, the building opens on May 29, 1889. Texans are satisfied that they have erected the most beautiful building in the world. They overlook a concurrent exposition across the Atlantic, where a man named Eiffel has just completed a remarkable tower. In colors and textures that resemble a gargantuan dried flower arrangement, the Spring Palace is an earthy monument. The Fort Worth Gazette observes, “Viewed from the distance of Front Street the Spring Palace appears the work of a genii… With its oriental towers silhouetted against the blue vault beyond, the rich, deep colors glistening in the sun, the banners flaunting in the gentle Texas breezes, music floating dimly in entrancing wavelets, the stranger is apt to stop short.”

Inside, the building’s walls are adorned in a continuation of the fantastic exterior. Against this backdrop, all of Texas is displayed with exuberant pride. The crazy-quilt floor plan of nooks and crannies bristles with exhibits of native woods, stone, and brick; minerals and ores; food, fibers, flowers, and furniture; insects, snakes, and lizards; a log cabin, a tepee, and a cave; historic relics, Texas patents, silkworms at work, and hundreds of live songbirds. What cannot be displayed firsthand is reproduced in large mosaic pictures and models, each fancifully rendered in native seeds, nuts, fish scales, or butterfly wings. In the rotunda, next to a large fountain stocked with game fish and ducks, the Elgin Watch Factory Band plays almost constantly. A local journalist calls the Palace “a bower of bewilderment.”

Advertised all across the nation, the Palace becomes an immediate tourist attraction—trains deliver the curious daily. Large registers at the Palace entrance record the arrival of visitors from every state in the nation. Though open for only three weeks, the exhibition is a fabulous success, and a second season is planned for the spring of 1890. An Austin newspaper writer dizzy with excitement editorializes (to no avail) that duplicates of the Palace be built in Chicago and New York City.

In its long off-season the Palace stands exposed to a year of weather. In the absence of flags flapping and bands playing, the wind can now be heard rustling the wheat that sheathes the huge central dome. On winter mornings the Palace waits silently, dusted with frost.

Two 100-foot-long extensions are added to the building for the 1890 season, and the hoopla continues. But on the evening of May 30th, during a grand ball in the Palace attended by thousands, the inevitable occurs. No one knows how the fire starts, but the building is quickly consumed like the architectural version of a prairie wildfire. Somehow, despite the disaster’s magnitude, there is only one fatality, a man who dies while rescuing others trapped in the Palace. It is a blaze of milestone proportions: At a time when America swoons at romantic calamities, the destruction of the Palace is front-page news nationwide. In fact, the death of the Texas Spring Palace is so spectacular that it overshadows accounts of the building’s fascinating life for nearly one hundred years. Those who remember, remember only the fire, while the “bower of bewilderment” is all but forgotten.