Starting Place

By Max Levy Texas Architect Magazine July 2002

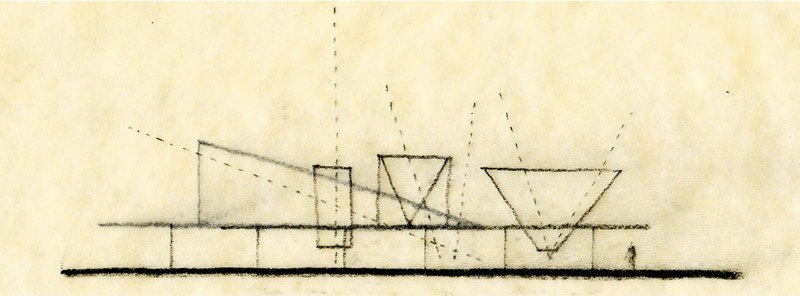

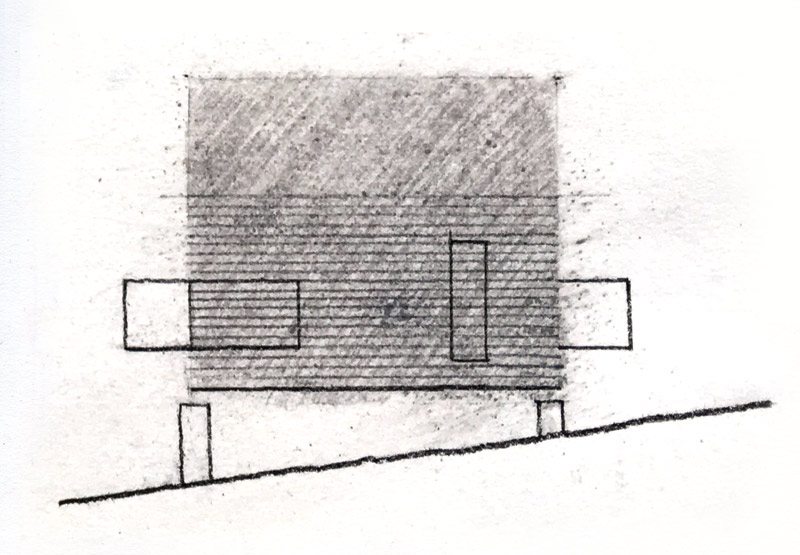

Milton Glaser, the eminent graphic designer, has said, “The creative act exists beneath the surface of your understanding.” That glow we admire in conceptual sketches does not arise from our conscious arrangement of pragmatics on paper, but from the intuition and inspiration that materialize on the page from somewhere else. These are not the drawings you show to your client; these are the drawings that show themselves to you. It is their mysterious mix of the imprecise with the dead-on that arrests our attention. Later, after the project is complete, we feel a sort of reverie that such a fleeting sketch so early on could accurately predict the content and atmosphere of a future place.

At the creative stage of things we architects operate along a borderline between dreaming and being. And when a sketch slips across this borderline into our hands, we automatically adore it like a newborn. No wonder these sketches make such an impression on us: while we struggle to bring our projects into being, doing battle with reality, and compromising along the way, these little drawings quietly keep the faith. They show us what the project can ideally be. They are therefore worth saving, to draw courage from for the moment and into the future.

Milton Glaser, the eminent graphic designer, has said, “The creative act exists beneath the surface of your understanding.” That glow we admire in conceptual sketches does not arise from our conscious arrangement of pragmatics on paper, but from the intuition and inspiration that materialize on the page from somewhere else. These are not the drawings you show to your client; these are the drawings that show themselves to you. It is their mysterious mix of the imprecise with the dead-on that arrests our attention. Later, after the project is complete, we feel a sort of reverie that such a fleeting sketch so early on could accurately predict the content and atmosphere of a future place.

At the creative stage of things we architects operate along a borderline between dreaming and being. And when a sketch slips across this borderline into our hands, we automatically adore it like a newborn. No wonder these sketches make such an impression on us: while we struggle to bring our projects into being, doing battle with reality, and compromising along the way, these little drawings quietly keep the faith. They show us what the project can ideally be. They are therefore worth saving, to draw courage from for the moment and into the future.

At last year’s TSA convention I presented a program about the initial conceptual work behind five projects underway in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. The architects represented were Steven Holl, Tadao Ando, Mockbee Coker, Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer, and Renzo Piano. Despite the broad design diversity of these firms, one phenomenon threads them all together: these architects don’t leave their initial sketches in the bottom of the drawer. Instead, they keep them out through the design and construction document process; they actually refer to them and prize what they have to say. Clearly, there is a connection between the idealism of initial sketches, the authority conferred upon them by their authors, and the artistic success of the projects which result.

The personal sketches of Steven Holl have recently become something of an artistic conscience for much of our profession. When many of us see this work published, we experience fascination, followed by a sense of regret that we don’t draw enough ourselves. Holl has said, “I consider (conceptual sketches) my secret weapon. They allow me to move afresh from one project to the next. If I approached projects with a fixed vocabulary, I would be exhausted by now; I would have lost my interest in architecture long ago.” The effect his sketches have upon his clients is intriguing. People in Holl’s office have told me they can show clients hard-edged drawings all day long and receive mild approval. But when the client is shown drawings from Holl’s own sketchbook, they tend to embrace the scheme wholeheartedly. In the blare of our media-hyped world sometimes the personal statement, delivered a cappella, penetrates more deeply.

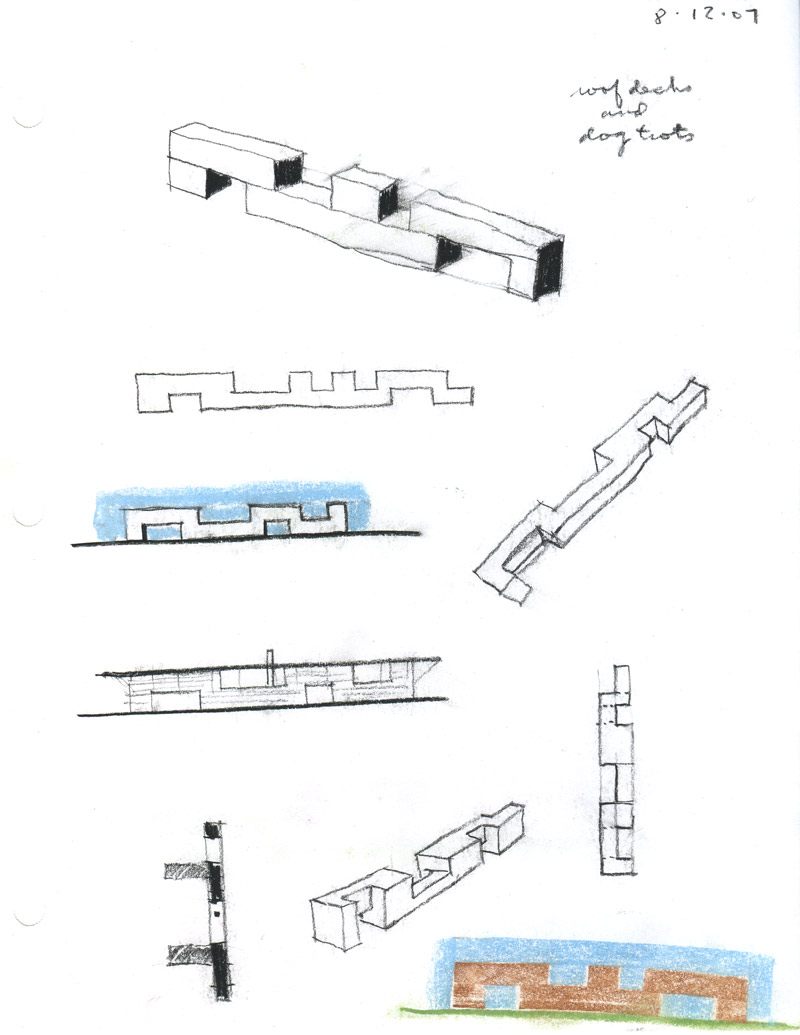

Early in a project, when Renzo Piano puts pen to paper, the results look like little musical scores with words, diagrams, and forms, all seemingly eliciting one another. Indeed, drawing assists thinking. It draws thoughts out of us which would not otherwise form if left inside our minds. Louis Kahn once observed, “oftentimes you imagine you are thinking when you are not, and this often happens when you are not drawing.” Too many of us have forgotten there is something magnetic in the act of drawing. Pre-conceptions confined in our heads for days almost invariably either blossom – or wither and then transform to something better – once you quietly doodle. The workings of such a modest act are vast and beyond comprehension—and central to our art.

There is a vague inertia to initiating a conceptual sketch, which if left unchallenged can become a barrier to communication with oneself. Past this inertia, however, one usually finds a momentum which lures more drawings out of you. As with physical exercise this action can begin with awkwardness, but ultimately result in some measure of grace. As he was dying, Michelangelo wrote a farewell note to his young apprentice. Distilling a lifetime of wisdom, the note said simply, “Draw, Antonio, draw, Antonio, draw and don’t waste time.” Tadao Ando carries a small sketchbook with him almost everywhere. It is a habit that developed early. Having received no formal architectural training, he began at age 18 to explain architecture to himself by sketching tea houses, shrines, and temples. Through his sketchbooks Ando continues to cast an ever wider net out into the world. Perhaps this is why his hushed architecture strikes us with such depth and intensity. Whether explaining the world to ourselves, resolving a problem, or exploring new territory, the act of drawing often opens a window to a gladdening view.

We would do well to coax out of ourselves a few of the many sketches and study models we routinely and increasingly talk ourselves out of doing. Most of us are so embattled at attempting to make a living at what we love doing that too much of the love has been crowded out of what we do. A significant part of the solution to this dilemma is to simply spend a little more time on each project at the starting place of our art. It is at this starting place that our conceptual artifacts bubble up. It is the same starting place that probably attracted many of us to wanting to be architects in the first place. If we can honor our instincts in this regard, not only will our work improve, but we will deepen our enjoyment of what it truly means to be an architect.

At last year’s TSA convention I presented a program about the initial conceptual work behind five projects underway in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. The architects represented were Steven Holl, Tadao Ando, Mockbee Coker, Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer, and Renzo Piano. Despite the broad design diversity of these firms, one phenomenon threads them all together: these architects don’t leave their initial sketches in the bottom of the drawer. Instead, they keep them out through the design and construction document process; they actually refer to them and prize what they have to say. Clearly, there is a connection between the idealism of initial sketches, the authority conferred upon them by their authors, and the artistic success of the projects which result.

The personal sketches of Steven Holl have recently become something of an artistic conscience for much of our profession. When many of us see this work published, we experience fascination, followed by a sense of regret that we don’t draw enough ourselves. Holl has said, “I consider (conceptual sketches) my secret weapon. They allow me to move afresh from one project to the next. If I approached projects with a fixed vocabulary, I would be exhausted by now; I would have lost my interest in architecture long ago.” The effect his sketches have upon his clients is intriguing. People in Holl’s office have told me they can show clients hard-edged drawings all day long and receive mild approval. But when the client is shown drawings from Holl’s own sketchbook, they tend to embrace the scheme wholeheartedly. In the blare of our media-hyped world sometimes the personal statement, delivered a cappella, penetrates more deeply.

Early in a project, when Renzo Piano puts pen to paper, the results look like little musical scores with words, diagrams, and forms, all seemingly eliciting one another. Indeed, drawing assists thinking. It draws thoughts out of us which would not otherwise form if left inside our minds. Louis Kahn once observed, “oftentimes you imagine you are thinking when you are not, and this often happens when you are not drawing.” Too many of us have forgotten there is something magnetic in the act of drawing. Pre-conceptions confined in our heads for days almost invariably either blossom – or wither and then transform to something better – once you quietly doodle. The workings of such a modest act are vast and beyond comprehension—and central to our art.

There is a vague inertia to initiating a conceptual sketch, which if left unchallenged can become a barrier to communication with oneself. Past this inertia, however, one usually finds a momentum which lures more drawings out of you. As with physical exercise this action can begin with awkwardness, but ultimately result in some measure of grace. As he was dying, Michelangelo wrote a farewell note to his young apprentice. Distilling a lifetime of wisdom, the note said simply, “Draw, Antonio, draw, Antonio, draw and don’t waste time.” Tadao Ando carries a small sketchbook with him almost everywhere. It is a habit that developed early. Having received no formal architectural training, he began at age 18 to explain architecture to himself by sketching tea houses, shrines, and temples. Through his sketchbooks Ando continues to cast an ever wider net out into the world. Perhaps this is why his hushed architecture strikes us with such depth and intensity. Whether explaining the world to ourselves, resolving a problem, or exploring new territory, the act of drawing often opens a window to a gladdening view.

We would do well to coax out of ourselves a few of the many sketches and study models we routinely and increasingly talk ourselves out of doing. Most of us are so embattled at attempting to make a living at what we love doing that too much of the love has been crowded out of what we do. A significant part of the solution to this dilemma is to simply spend a little more time on each project at the starting place of our art. It is at this starting place that our conceptual artifacts bubble up. It is the same starting place that probably attracted many of us to wanting to be architects in the first place. If we can honor our instincts in this regard, not only will our work improve, but we will deepen our enjoyment of what it truly means to be an architect.