Carlo Scarpa in Person

By Max Levy Cite Magazine Summer 2008

When one turns the page of an architecture magazine and the work of Carlo Scarpa appears unexpectedly, a quiet inner thrill is felt. Since his passing in 1978, we seem increasingly moved by Scarpa’s caress of material, his strange but faultless sense of placement and proportion, the contemplative nature of his details. These appreciations are heightened by the knowledge that his output was relatively limited. Confined mostly to the floating world of Venice and a few other Italian sites, his work tantalizes by its rarity and distance from us. It may come as a revelation therefore to learn that Scarpa executed a project here in America. Seen by very few people, the project remained intact for merely one month, and only a few mediocre photographs survive.

In March of 1969 the University Art Museum at the University of California at Berkeley mounted an engaging exhibition. It consisted of 146 tiny but epic architectural sketches by Eric Mendelsohn, the great German early Modernist. The drawings were presented in an installation of architectural stagecraft designed by the then-obscure Scarpa. I was an architecture student at Berkeley at the time and wandered into this confluence of masters.

Though I knew a bit about Mendelsohn from my architecture history courses, my introduction to Scarpa was to be up close and in person. He came to Berkeley to refine the exhibition design onsite and to personally supervise its installation. A few days before the show opened a small poster announced that a Professor Scarpa would lecture on his work that evening. Though the eminent historian, Vincent Scully, would eventually place Scarpa “somewhere between Wright and Kahn”, I found no one at the school that day who had ever heard of him. I went to the lecture anyway. In a room that would have seated three hundred people, only five showed up. This aroused much animated discussion between Scarpa and his interpreter, and soon we heard from the lectern, “Professor Scarpa feels this room is too large for such a small group. We must move to a space better tailored to the scale of the gathering”. Already this guy had my attention.

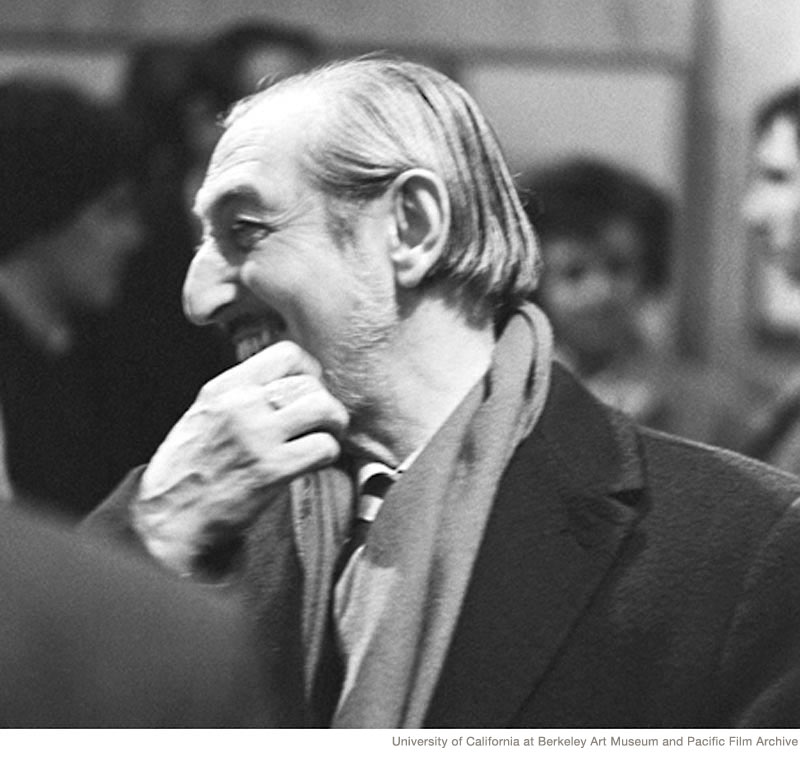

It took thirty minutes for the big university to find us another room. Meanwhile Scarpa waited with genial forbearance, chain-smoking, smiling over at us occasionally. We sat there silently, too self-conscious to bale out of an awkward situation. At last a smaller room was assigned all the way across campus, and away the whole group marched. It was like a scene from a Fellini movie: nightfall, the Pacific fog rolling in, the AV guy in the lead pushing his slide projector on a noisy metal cart, then came Scarpa in his gorgeous sport coat and long woolen scarf, followed by his interpreter, and the rag-tag audience of five.

The new room was fitting, the images were projected in the dark, and my jaw dropped. We saw a travertine door, a plaster ceiling polished to an almost mirror finish, fittings combining cast iron, bronze and rosewood, rooms loosely defined by planes of luscious materials dissolving into shadow, windows like glass boxes of light, and a birdbath so poetic it touched the heart. We saw the Museo Correr, the Canova Gallery, the Olivetti Shop, the Querini Stampalia, the Castelvecchio. And we saw schematic drawings for a work in progress, the Brion Cemetery. Each drawing teemed from margin to margin with ideas in embryo, some precisely delineated, others, a mist of color and spirit. As the jewel-like images were projected, Scarpa kept up a vivacious commentary in Italian. He stood next to the slide projector in the middle of the room facing the screen with the audience, his face grotesquely uplit, deeply inhaled cigarette smoke vaporing forth luminously as he spoke. That evening this friendly dragon conveyed an unforgettable sensitivity to materials and details and space.

Eric Mendelsohn was a contemporary of Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and Arnold Schonberg. Up until the 1960’s, when his reputation began to fade, he was often grouped with the founding masters of Modernism. His career was launched by the remarkable conceptual sketches presented in the Berkeley exhibition. Most of these drawings were about the size of a note card, some no larger than a postage stamp. Many were drawn on scraps of paper in the trenches of World War I where he fought on the Russian front for the Kaiser. In a few miniature but bold strokes of black ink or pencil we see buildings of unprecedented dynamism, seemingly rushing forward into a hopeful future. They were also unusual for the way they depicted buildings spatially, seen from an angle, instead of flattened and static in the plan/section/elevation tradition. After the war Mendelsohn’s years of imaginary sketches sprang to life in real commissions. Defined by an unusual blend of pragmatics and expressionism, his work is linked with trends reemerging today though never credited to him.

The exhibition’s setting was a windowless brown brick Romanesque building, roofed by a single gable with a large ridge skylight of steel and wire-glass. Inside was a space about the size of a basketball court. Built in 1905, it served as the university’s power house until the 1930’s, when it was picked clean and given over to gallery space. The building sat in the shade of oaks and old growth redwoods next to Strawberry Creek, a dark cathedral-like sliver of nature that tumbles down through the hilly campus. This bucolic scene contrasted markedly with the university’s political and emotional atmosphere. It was an ungovernable mass of protest over the Viet Nam War, the civil rights movement, sexual liberation, pacifism, feminism, and free speech. Just fifty yards away from the brown brick building was Sproul Plaza, ground zero for leafleteers, demonstrations, and glimpses of anarchy.

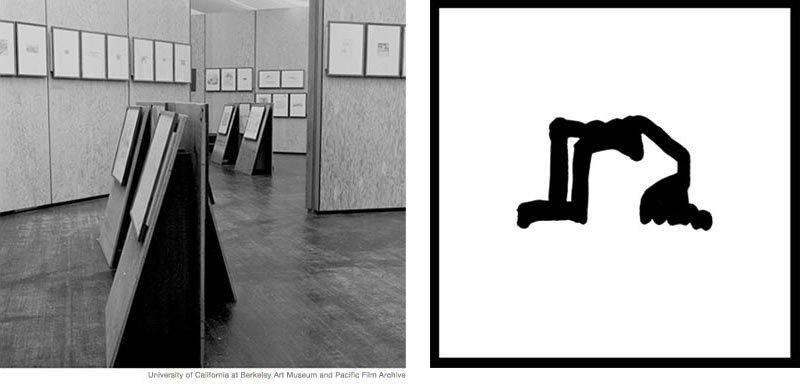

Designing the exhibition presented Scarpa with two immediate hurdles. First there was the project budget. Accustomed to working with lavish materials, the virtuoso designer would be limited in Berkeley to little more than plywood. Welcome to America. Secondly, the power house space was far too big for the display of little drawings. Once again Scarpa concerned himself with refashioning a venue so that it would be “tailored to the scale of the gathering”. Using eight foot tall panels of fir plywood, he tightly defined a smaller space in the center of the room. In plan view it was jagged, something like a stroke of lightning. The remainder of the power house was rendered as inaccessible poche. The panels were stained either red-orange or loden green, and were detailed so that the plywood edge laminations were frankly revealed. The Mendelsohn drawings with their concentrated black strokes, oversized creamy white mats, and wooden frames stained nearly black, looked exquisite against the strangely colored gallery walls. Smaller drawings were hung somewhat higher than normal, meeting one’s gaze eye to eye. By contrast, the larger drawings required a bow of the head. They were mounted on low plywood lean-to’s, peculiar fractured remnants that created spatial eddies in the gallery. A tiny detail: the inside corners of the mat cutouts were radiused, expressing tender regard for the drawings’ frailty and organic lines. Overhead the scale of the space was reduced by suspending swaths of white silk in the horizontal plane. There was no artificial lighting of any kind. Soft Northern California sunshine poured through the big skylight, filtered through the silk, and filled the place with a chiaroscuro of liquid calm.

When one turns the page of an architecture magazine and the work of Carlo Scarpa appears unexpectedly, a quiet inner thrill is felt. Since his passing in 1978, we seem increasingly moved by Scarpa’s caress of material, his strange but faultless sense of placement and proportion, the contemplative nature of his details. These appreciations are heightened by the knowledge that his output was relatively limited. Confined mostly to the floating world of Venice and a few other Italian sites, his work tantalizes by its rarity and distance from us. It may come as a revelation therefore to learn that Scarpa executed a project here in America. Seen by very few people, the project remained intact for merely one month, and only a few mediocre photographs survive.

In March of 1969 the University Art Museum at the University of California at Berkeley mounted an engaging exhibition. It consisted of 146 tiny but epic architectural sketches by Eric Mendelsohn, the great German early Modernist. The drawings were presented in an installation of architectural stagecraft designed by the then-obscure Scarpa. I was an architecture student at Berkeley at the time and wandered into this confluence of masters.

Though I knew a bit about Mendelsohn from my architecture history courses, my introduction to Scarpa was to be up close and in person. He came to Berkeley to refine the exhibition design onsite and to personally supervise its installation. A few days before the show opened a small poster announced that a Professor Scarpa would lecture on his work that evening. Though the eminent historian, Vincent Scully, would eventually place Scarpa “somewhere between Wright and Kahn”, I found no one at the school that day who had ever heard of him. I went to the lecture anyway. In a room that would have seated three hundred people, only five showed up. This aroused much animated discussion between Scarpa and his interpreter, and soon we heard from the lectern, “Professor Scarpa feels this room is too large for such a small group. We must move to a space better tailored to the scale of the gathering”. Already this guy had my attention.

It took thirty minutes for the big university to find us another room. Meanwhile Scarpa waited with genial forbearance, chain-smoking, smiling over at us occasionally. We sat there silently, too self-conscious to bale out of an awkward situation. At last a smaller room was assigned all the way across campus, and away the whole group marched. It was like a scene from a Fellini movie: nightfall, the Pacific fog rolling in, the AV guy in the lead pushing his slide projector on a noisy metal cart, then came Scarpa in his gorgeous sport coat and long woolen scarf, followed by his interpreter, and the rag-tag audience of five.

The new room was fitting, the images were projected in the dark, and my jaw dropped. We saw a travertine door, a plaster ceiling polished to an almost mirror finish, fittings combining cast iron, bronze and rosewood, rooms loosely defined by planes of luscious materials dissolving into shadow, windows like glass boxes of light, and a birdbath so poetic it touched the heart. We saw the Museo Correr, the Canova Gallery, the Olivetti Shop, the Querini Stampalia, the Castelvecchio. And we saw schematic drawings for a work in progress, the Brion Cemetery. Each drawing teemed from margin to margin with ideas in embryo, some precisely delineated, others, a mist of color and spirit. As the jewel-like images were projected, Scarpa kept up a vivacious commentary in Italian. He stood next to the slide projector in the middle of the room facing the screen with the audience, his face grotesquely uplit, deeply inhaled cigarette smoke vaporing forth luminously as he spoke. That evening this friendly dragon conveyed an unforgettable sensitivity to materials and details and space.

Eric Mendelsohn was a contemporary of Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and Arnold Schonberg. Up until the 1960’s, when his reputation began to fade, he was often grouped with the founding masters of Modernism. His career was launched by the remarkable conceptual sketches presented in the Berkeley exhibition. Most of these drawings were about the size of a note card, some no larger than a postage stamp. Many were drawn on scraps of paper in the trenches of World War I where he fought on the Russian front for the Kaiser. In a few miniature but bold strokes of black ink or pencil we see buildings of unprecedented dynamism, seemingly rushing forward into a hopeful future. They were also unusual for the way they depicted buildings spatially, seen from an angle, instead of flattened and static in the plan/section/elevation tradition. After the war Mendelsohn’s years of imaginary sketches sprang to life in real commissions. Defined by an unusual blend of pragmatics and expressionism, his work is linked with trends reemerging today though never credited to him.

The exhibition’s setting was a windowless brown brick Romanesque building, roofed by a single gable with a large ridge skylight of steel and wire-glass. Inside was a space about the size of a basketball court. Built in 1905, it served as the university’s power house until the 1930’s, when it was picked clean and given over to gallery space. The building sat in the shade of oaks and old growth redwoods next to Strawberry Creek, a dark cathedral-like sliver of nature that tumbles down through the hilly campus. This bucolic scene contrasted markedly with the university’s political and emotional atmosphere. It was an ungovernable mass of protest over the Viet Nam War, the civil rights movement, sexual liberation, pacifism, feminism, and free speech. Just fifty yards away from the brown brick building was Sproul Plaza, ground zero for leafleteers, demonstrations, and glimpses of anarchy.

Designing the exhibition presented Scarpa with two immediate hurdles. First there was the project budget. Accustomed to working with lavish materials, the virtuoso designer would be limited in Berkeley to little more than plywood. Welcome to America. Secondly, the power house space was far too big for the display of little drawings. Once again Scarpa concerned himself with refashioning a venue so that it would be “tailored to the scale of the gathering”. Using eight foot tall panels of fir plywood, he tightly defined a smaller space in the center of the room. In plan view it was jagged, something like a stroke of lightning. The remainder of the power house was rendered as inaccessible poche. The panels were stained either red-orange or loden green, and were detailed so that the plywood edge laminations were frankly revealed. The Mendelsohn drawings with their concentrated black strokes, oversized creamy white mats, and wooden frames stained nearly black, looked exquisite against the strangely colored gallery walls. Smaller drawings were hung somewhat higher than normal, meeting one’s gaze eye to eye. By contrast, the larger drawings required a bow of the head. They were mounted on low plywood lean-to’s, peculiar fractured remnants that created spatial eddies in the gallery. A tiny detail: the inside corners of the mat cutouts were radiused, expressing tender regard for the drawings’ frailty and organic lines. Overhead the scale of the space was reduced by suspending swaths of white silk in the horizontal plane. There was no artificial lighting of any kind. Soft Northern California sunshine poured through the big skylight, filtered through the silk, and filled the place with a chiaroscuro of liquid calm.

Over its short run I visited the exhibition three times. On each occasion I was the only one there. Noisy outside and quiet inside, the show was swept to the margins by campus upheaval. Arts reporters made no mention of it in the cultural press. The show’s only print media appearance was a superb little seven inch square exhibition catalog, which is surprisingly still available for sale online after all these years.

Neither Mendelsohn nor Scarpa were strangers to this backdrop of turmoil. Mendelsohn’s career, launched by World War I and mortally wounded by World War II, was one of the great reversals of fortune of the Modern Movement. In the interwar period, his was one of the largest architectural practices in Germany, doing prestigious projects while advancing artistically. His success was begrudged by the Bauhaus circle, and was soon snuffed out altogether by the Nazis. The Jewish architect abruptly closed his thriving office, emigrating first to London, then to Jerusalem, and finally to San Francisco. Though he produced some remarkable buildings at each stop, his promise as an international form-giver seemed to fade away in Northern California. Scarpa’s career was marked by conflict in Italy, first with the communists, then with the fascists, and all along with the Italian architectural community which never admitted him to the profession in his lifetime. Just before coming to Berkeley he had a run-in with his own architecture students at the University of Venice. At some peril to his own wellbeing, he tore down their banners of protest, not because he disagreed with them politically, but because he thought the banners’ lettering was disgraceful.

One wonders how Scarpa regarded his sole American performance. When Louise Mendelsohn, Eric’s widow, invited him to design the show, he was so pleased with the honor and the prospect that he waived his fee, asking only that his expenses be reimbursed. Despite the meager budget he was presented with, he must have been buoyed to learn that much of the funding was made possible by John Entenza, legendary editor of Arts and Architecture magazine, founder of the Case Study House program, and at that time Director of the Graham Foundation. Soon after Scarpa’s arrival in Berkeley the art museum suggested to the architecture school that it might want to have him address the students. The school offered the maestro a $50 honorium for his lecture. And then there was the very American project schedule: he accepted Louise’s invitation in January, arrived in February, and the show opened in March. It is recorded that he referred to the carpenter assigned to the installation as his “lumberjack”, though it is unclear whether this was an affectionate term for a big fellow in flannel shirt and jeans, or an expression of frustration over the carpenter’s coarse workmanship.

After the exhibition closed it was offered as a traveling package to several museums around the country. Interestingly, two of them were the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts and the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, both of whom turned the show down. It did however travel to MOMA in New York, but only the framed Mendelsohn drawings made the trip. The plywood panels wound up in a university store room, no doubt to be scavenged over the years for utilitarian purposes by an unwitting maintenance staff.

In retrospect I have to admit, though I was intrigued by the lecture and exhibition, I didn’t fully appreciate at the time what I had wandered into. That appreciation has taken years to mature, to be deepened by exposure to Scarpa’s broader works, to be measured against my own modest attempts at wresting some degree of artistry from an obstinate world. The farther away I recede in time from that lecture, the more often it seems to revisit me at odd moments. As for the exhibition itself, I know now it was a dimmed version of Scarpa’s full powers. And yet, denied his typical formula of rich materials, master artisans, and long gestation, he still managed somehow to engage the eye, the mind, and the heart. In that gallery was a wood-grained environment of uncommon warmth, tinged with the color scheme of the Third Reich, laid out in a geometric anguish unlike any other floor plan of the time. And all of it, down to the cut of the mat board, amplifying the distant thunder of Mendlesohn’s brilliant little drawings.

Over its short run I visited the exhibition three times. On each occasion I was the only one there. Noisy outside and quiet inside, the show was swept to the margins by campus upheaval. Arts reporters made no mention of it in the cultural press. The show’s only print media appearance was a superb little seven inch square exhibition catalog, which is surprisingly still available for sale online after all these years.

Neither Mendelsohn nor Scarpa were strangers to this backdrop of turmoil. Mendelsohn’s career, launched by World War I and mortally wounded by World War II, was one of the great reversals of fortune of the Modern Movement. In the interwar period, his was one of the largest architectural practices in Germany, doing prestigious projects while advancing artistically. His success was begrudged by the Bauhaus circle, and was soon snuffed out altogether by the Nazis. The Jewish architect abruptly closed his thriving office, emigrating first to London, then to Jerusalem, and finally to San Francisco. Though he produced some remarkable buildings at each stop, his promise as an international form-giver seemed to fade away in Northern California. Scarpa’s career was marked by conflict in Italy, first with the communists, then with the fascists, and all along with the Italian architectural community which never admitted him to the profession in his lifetime. Just before coming to Berkeley he had a run-in with his own architecture students at the University of Venice. At some peril to his own wellbeing, he tore down their banners of protest, not because he disagreed with them politically, but because he thought the banners’ lettering was disgraceful.

One wonders how Scarpa regarded his sole American performance. When Louise Mendelsohn, Eric’s widow, invited him to design the show, he was so pleased with the honor and the prospect that he waived his fee, asking only that his expenses be reimbursed. Despite the meager budget he was presented with, he must have been buoyed to learn that much of the funding was made possible by John Entenza, legendary editor of Arts and Architecture magazine, founder of the Case Study House program, and at that time Director of the Graham Foundation. Soon after Scarpa’s arrival in Berkeley the art museum suggested to the architecture school that it might want to have him address the students. The school offered the maestro a $50 honorium for his lecture. And then there was the very American project schedule: he accepted Louise’s invitation in January, arrived in February, and the show opened in March. It is recorded that he referred to the carpenter assigned to the installation as his “lumberjack”, though it is unclear whether this was an affectionate term for a big fellow in flannel shirt and jeans, or an expression of frustration over the carpenter’s coarse workmanship.

After the exhibition closed it was offered as a traveling package to several museums around the country. Interestingly, two of them were the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts and the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, both of whom turned the show down. It did however travel to MOMA in New York, but only the framed Mendelsohn drawings made the trip. The plywood panels wound up in a university store room, no doubt to be scavenged over the years for utilitarian purposes by an unwitting maintenance staff.

In retrospect I have to admit, though I was intrigued by the lecture and exhibition, I didn’t fully appreciate at the time what I had wandered into. That appreciation has taken years to mature, to be deepened by exposure to Scarpa’s broader works, to be measured against my own modest attempts at wresting some degree of artistry from an obstinate world. The farther away I recede in time from that lecture, the more often it seems to revisit me at odd moments. As for the exhibition itself, I know now it was a dimmed version of Scarpa’s full powers. And yet, denied his typical formula of rich materials, master artisans, and long gestation, he still managed somehow to engage the eye, the mind, and the heart. In that gallery was a wood-grained environment of uncommon warmth, tinged with the color scheme of the Third Reich, laid out in a geometric anguish unlike any other floor plan of the time. And all of it, down to the cut of the mat board, amplifying the distant thunder of Mendlesohn’s brilliant little drawings.